An open letter to Pledgers

The gaming crowdfunding sector is in crisis, but Monolith is more resilient than ever

Hello,

You will all have noticed that the gaming crowdfunding sector is undergoing the first crisis of its relatively short lifespan so far. This is partly tied to the more general economic crisis that has gripped the gaming sector as a whole since the end of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, it has been enormously amplified by the terrible crisis of confidence caused and by the past, present, and likely future failures of companies with dubious business practices. I have spent many years warning against such practices (in articles, on websites, and on social media) and the risks they pose to the entire sector. I have also advocated for rigor over extravagance, professionalism over promises. Today, I feel obliged to intervene once again, to explain that it is irrational to punish the Ants for mistakes made by the Grasshoppers, to paraphrase Aesop’s fable. Some companies in our sector are reliable and in good health; they have capital, cash flow, and a small payroll, and they are rigorously managed by experienced people. Monolith is one of them.

A crisis driven by a wave of delivery failures

Companies default on deliveries for a simple (basically mechanical) reason. Although not necessarily deliberately or maliciously, these companies will have been “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” meaning that the funds raised among backers to finance a project were, at least partially, actually used to finance something else (basically, financing previous projects that would otherwise have failed to reach their required funding goals). It should also be noted that the “funding goals” listed on crowdfunding projects are almost always completely arbitrary, and never represent more than a fraction of a project’s actual break-even amount. In ten years of crowdfunding, I have only ever seen two funding goals that corresponded to a project’s actual needs: once on Claustrophobia, whose goal corresponded to one box, since the entire project had already been produced; and once on Beyond the Monolith, which was actually a disaster overall, and during which I made the mistake of entering the true funding goal of $700K. Generally speaking, the funding goals displayed are systematically false, because pledgers want stretch goals, and these stretch goals can only start after $700K or $800K, or even a million euros for most major projects. So-called “goals” are therefore little more than trigger points for stretch goals (which themselves have no function other than providing entertainment, as they are planned prior to launch and their distribution during a campaign is simply part of its pacing, divorced from any profitability considerations). If the campaign is moving fast, the SGs will be spaced out, otherwise they will be tightened up, but whatever happens the content of the campaign will be exactly the same. To return to our previous point, the economic crisis does not explain delivery failures. If funds from previous projects had been sufficient and correctly used for said projects, then the drop in funding for new projects would have no impact on the delivery of previous ones. The only two explanations for delivery failures are the misallocation of funds raised (using them for something other than their intended purpose), or not raising enough funds in the first place.

To understand how a crowdfunding company can quickly fall into this practice of “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” we must take a closer look at the economic structure of a given project.

Let’s take a typical project offering a large board game with miniatures (such as Mythic Battles: Isfet). For the sake of clarity, let’s assume that the game is entirely the property of the publisher (i.e., with no copyright fees involved) and has no license (as is the case with Isfet).

Let’s then imagine that this project raises $1000K on a platform (KS, Gamefound, or any other).

During the Pledge Manager, this amount will typically increase by around 20% in additional sales, excluding VAT, to which will be added around 25% in shipping costs and 10% in VAT (roughly half of all shipping countries are subject to VAT). So $1M + $200K + $300K + $150K = $1.65M. Based on this amount, the various platforms and other payment intermediaries will deduct around 9% in total. This leaves approximately $1.5M in the project owner’s bank account.

In the miniature board game crowdfunding sector, the price of products is around four times their variable production cost. So, in our example, manufacturing $1.2M of merchandise ($1000K during KS and $200K during the PM), costs around $300K.

So, from the original $1.5M after paying platform fees, we have to deduct $150K in VAT, $60K in containers (approximately $12/pledge), $300K in last mile delivery, and $300K in manufacturing. In total, this comes to $810K (which is more than 50% of the funds raised overall). For a classic large-scale project (such as Conan or MB), we would have to subtract around $250K for molds and $300K for development (illustrations, sculptures, and, above all, the salaries of everyone working on the project). This leaves a total margin of $140K on the $1.650M spent by backers and the $1.5M received by the project owner (around a 10% margin, which is lower than in the retail publishing sector, and can be explained by the relatively low amount raised during the campaign, which is nonetheless realistic given the current lack of trust in crowdfunding).

| Income | Campaign | $ 1000K |

| Extra revenue excl. tax (PM) | $ 200K | |

| Shipping (PM) | $ 300K | |

| VAT (PM) | $ 150K | |

| Expenses | KS, Gamefound, Stripe, etc. | $ 150K |

| Internal and external development (overhead costs) | $ 300K | |

| Molds | $ 250K | |

| Production | $ 300K | |

| Containers | $ 60K | |

| Shipping | $ 300K | |

| VAT | $ 150K | |

| Total | $ 140K |

Looking at these figures, it would be very easy to mistakenly think that, because $300K is enough to pay for production, we have an enormous amount of leeway thanks to the $1.5M we have in the bank. What’s more, the specific timing of a project’s financial obligations (funds are received far in advance of production, delivery and, until recently, payment of VAT) makes it even harder to decipher these figures. Let’s imagine that the project owner has four or five similar projects waiting to be delivered. In this case, they may find themselves with between $6M and $7.5M in cash, and quite naturally get the mistaken impression of being rich. The problem with crowdfunding companies is that they are literally awash with cash…until the time comes to deliver. At that point, the slightest miscalculation in production costs, shipping costs or, above all, development costs, can quickly drive a company over the edge.

Chronic delays are by far the driving factor for failures among crowdfunding companies

Of all the above-mentioned costs, development costs are by far the most likely to increase sharply. This is due to one simple factor: delays, which inevitably generate additional costs due additional payroll (and therefore time) along with other overheads involved in a project. Imagine a company with 15-20 employees. It will very quickly exceed $1000K in overheads (gross salaries + office space + miscellaneous costs). Let’s imagine that the company in question can work simultaneously on five projects similar to the one in our example (which, for 15-20 employees, is entirely feasible). In one year, an average of $200K in overheads would be allocated to each of these projects. Now let’s imagine that the five projects raised $7.5M in total and were each delivered six months late. They would therefore incur additional costs of $500K ($100K per project). So, of the $700K profit theoretically generated, only $200K remains. And this is in the case of “only” six months’ delay for five projects, yet overall profits have just plummeted to less than 3%. Delays are by far the most damaging factor for project owners, much more than external factors such as the price of raw materials, containers, or even production costs.

For example:

- • The price of raw materials makes up no more than 20% of production costs for molds and 10% for the products themselves. This corresponds to around 15% of the total production cost. Therefore, a 25% increase in the price of raw materials would lead to a 5% increase in the cost of the molds ($12.5K) and 2.5% in the cost of production ($7.5K). In total, this would translate into an additional cost of $20K per project, which is far less than the $100K generated by a six-month delay.

- • The cost of containers for a campaign like Mythic Battles at $1.5M at the end of the PM is around $60K. An increase of 30% would lead to an additional cost of $18K per project (once again, a far cry from the $100K due to a six-month delay).

- • An increase of 10% in total production costs (both variable and fixed) would lead to an additional $60K in costs of each project – barely more than half of the increase generated by just six months’ delay.

In other words, for our type of campaign (conventional board game campaigns with miniatures) and for a company with 15-20 employees, a six-month delay corresponds to a 500% increase in the cost of raw materials, almost triple the cost of containers, and a 20% increase in all production costs (both fixed and variable). Once again, this is by far the most important factor explaining the success or failure of a crowdfunding company.

To avoid falling into this trap, Monolith transformed its model two years ago. In the new system, campaigns are never launched until the development phase is finished

The most observant crowdfunding backers will have noticed that, since May 2022 (after the Batman RPG campaign), Monolith almost completely withdrew from public posting – other than for the OrcQuest mini-campaign. This silence continued until 2024. During this period of “down time,” we completely overhauled our processes. Given our repeated delays (particularly on Batman RPG and even more so on MBR), and for the reasons given above, it had become essential for us to finalize the development phase before launching a campaign. Our aim was twofold: to know our development costs to the nearest dollar, and to never fall behind schedule again.

The subsequent 18 months were then devoted to developing the Red Nails campaign (fully completed before the launch), the Solomon Kane RPG campaign (fully completed before the launch), the MB Isfet campaign (fully completed before the launch), the Batman RPG 2 campaign (fully completed before the launch), and the Conan RPG campaign (set to be fully completed before the launch). Over the last year and a half, we have also been finalizing our current projects (MBR and Batman RPG) and developing future ones. Today, aside from a major catastrophic event (such as another global pandemic or a war between the U.S.A. and China), we have total control over our post-campaign schedule. From now on, campaigns will be delivered with the same respect for deadlines as seen with OrcQuest. The 18 months of “low-profile public activity” have therefore been very intense in terms of work and investment behind the scenes (including the acquisition of licenses and game development; more than one million euros have been allocated to preparing for 2024, 2025, and 2026).

Why is it so important to guarantee that development has been fully paid before the start of the campaign?

This is because, if we look at the table above, we can see that the $300K for development costs is no longer the responsibility of the campaign, as it has already been paid for by profits made on previous campaigns or cash contributions from shareholders. (We are therefore doing the opposite of “robbing Peter to pay Paul”). Therefore, in order to deliver the games, only $1.06M of the $1.5M raised by the project owner is actually required. Not a single dollar is allocated to “completing the game.” Of course, this doesn’t mean that profits are now $440K (they are still $140K); it is simply that the risks inherent to the development of the game are no longer pushed onto backers, as this phase has already been financed by the project owner. If we exclude exclusively transferable costs (VAT and shipping costs, which are simply collected and paid on by the project owner), out of the $1.04M in pure sales (meaning focused on the purchase of the game itself), only $550K (approximately half) is enough to cover all production costs (both fixed and variable). In other words, and without impacting margins, when development has been paid for in full prior to the campaign (and VAT and shipping costs have been set aside to avoid misusing them to artificially bulk up available cash flow), a campaign requires much less money to ensure delivery, even in the case of negative profits.

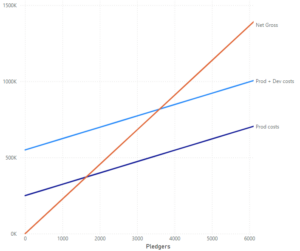

Break-even points and deliverability thresholds

So long as all development costs have already been paid, and so long as shipping costs and VAT have been correctly calculated and collected, simply financing production costs (both fixed and variable) is enough to deliver a campaign. In our example, $1.2M was spent by backers on the games themselves (excluding tax and shipping costs). For an average purchase of $250 (which is the average purchase amount for this type of campaign at Monolith, after the “fake” $1 pledges have been extracted), that gives us a post-PM total of 4,800 “real” backers, with the average variable production cost (excluding molds) of a game totaling $250/4 = $62.5. We must then add the average cost of transporting each pledge to its respective hub (approximately $12). The campaign’s “deliverability” threshold is therefore the point at which the number of pledgers and the average pledge (excluding KS, PM, Stripe direct debits: 9%) exceeds the total fixed production costs (molds) and variable costs (the variable percentage of production costs and containers).

The break-even point

Profitability: (x)($250)(0.91) = $550,000 + (x)($62.5)+(x)($12)

Therefore: (x)($153) = $550,000

Which gives us, approximately: x = 3,595 backers for $899,000

The Deliverability Threshold

As the development phase is already complete and paid for, the true deliverability threshold for this campaign is therefore (x)($250)(0.91) = $250,000 + (x)($62.5)+(x)($12)

Therefore: (x)($227.5) -(x)($74.5) = $250,000

Therefore: (x)($153) = $250,000

Which gives us, approximately: 1,634 backers for $408,000

So, while 3,595 pledgers and $899K are needed to break even, only 1,634 pledgers and $408K are needed to ensure the project’s successful delivery without any external contribution, so long as the entire development phase has already been paid for by the project owner. In our example, despite profitability of -45%, the project remains perfectly deliverable without any external contribution whatsoever.

It is therefore essential to understand that completing the development phase of a project significantly reduces its risk of failure, regardless of whether it breaks even or not. This also means that, when a project is unfinished, every hour of additional development brings the project’s deliverability threshold closer to its break-even point.

But if deliverability is so achievable, why are there so many failures?

Because while one-off negative profitability doesn’t necessarily compromise a project’s deliverability (see above), chronic negative profitability naturally leads to “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” at least to some extent. The accumulated debt from previous campaigns impacts the cash flow of current campaigns, with funds diverted from their intended purpose (for example, using money from current shipping costs and VAT to pay for the production and delivery of a previous project, making the current project dependent on the results of the following project). Once again, the biggest factor in the debt incurred by previous campaigns is additional development costs caused by delays.

Occasionally insufficient funds raised to guarantee the financing of projects

The second factor (after delays) influencing delivery failures is often inadequate fundraising during campaigns, and more specifically project owners refusing to cancel a campaign despite it not reaching its deliverability threshold, let alone its break-even point (see above).

Once again, the “funding goals” listed on crowdfunding campaign pages have no rational basis. They represent little more than the limit at which stretch goals are “offered.” Crowdfunding platforms do not require any “profit & loss” documents verifying the feasibility of a project before it is pitched to the public. Project owners are free to promote just about anything they want, and as we have seen time and time again, many are doing just that (Monolith included).

Every time a project owner cancels a campaign that has reached and exceeded its so-called “funding goal” (which is actually a stretch goal limit), they are torn apart on social media. Yet in reality, this is proof of exceptional professionalism; a project owner refusing to take the money in the knowledge that it will not be enough to complete the project. In doing so, they avoid backers having to shoulder the cost. In this scenario, backers have not had their pledges taken from them, while the project owner has in fact wasted their own time and money preparing the project. On a personal level, I truly admire project owners who are able to turn down the $600,000 or $700,000 that they could have collected at the time, simply because they know that this money will not be enough to guarantee the project’s future deliverability. I see this as a sign of trust. The outrage and hate that these situations provoke online is likely due to the fact that, by cancelling, the project owner is admitting that the goal they entered was wrong. However, they are only admitting what everyone already knows. I sincerely believe that backers who still think, in 2024, that goals of $200,000 are enough to deliver a miniature game project that isn’t a reprint, should take some time off from crowdfunding and brush up on their knowledge of fixed development and production costs. Insofar as backers have the option of withdrawing their pledge (meaning their promise of funding) right up until the last second, it seems perfectly natural to me that, in return, the project owner should also be able to withdraw their project up until the end of the campaign. The sector would be in much better shape if platforms demanded rigorous profit & loss documentation from project owners, which would enable them to set realistic deliverability thresholds for projects (and the more progress made on the development phase, the lower the deliverability threshold, see above). In my opinion, the ideal situation would be – at least in the case of large-scale projects – for crowdfunding platforms to impose funding goals equivalent to the deliverability threshold as defined through careful analysis of detailed profit & loss documents. This is the only way to restore backers’ trust.

With that in mind, what tools and advantages does Monolith have, how am I able to promise you that we will ALWAYS deliver the products that we have sold?

Monolith will always deliver the products that it sells. Always. And to achieve this promise, we have a whole host of tools and advantages at our disposal:

- Small payroll: Monolith has only six employees, that’s all! Not a single one more. We are far from the 20 employees from the previous example. We are an ultra-lean organization and therefore unburdened by large payroll. What’s more, neither of our two shareholders takes any salary or dividends from the company; all our profits are reinvested in the form of investments.

- An expanding company: Monolith is growing. We have recently emerged from a period of major investments and acquisitions (including the acquisition of the Solomon Kane and Reichbusters IPs, the acquisition of Rackham Entertainment’s IPs, the signing of the L5R and Berserk IPs, and ongoing acquisition of other IPs that we have to keep secret for now). Monolith has used the crisis to build a significant catalog at a lower cost.

- Highly experienced leaders with significant resources: Monolith is run by industry veterans who decided join forces and have fun working together. None of us rely on Monolith to live. I have had works published for 20 years and I have been a professional author for more than 15 years. I have more sold more than four million games spread over some 20 titles (including The Adventurers, Conan, Timeline, Cardline, The Builders, and Star Wars Bounty Hunters). Meanwhile, Marc (Nunès) is quite simply the most successful entrepreneur in gaming history. Starting with the equivalent of $8,000 some 35 years ago, he founded and directed Asmodee until it became the multi-billion-dollar giant everyone knows today. He enjoys an exceptional reputation, and he is now the one steering Monolith. It also goes without saying that Marc and I would rather refinance the company using our own funds than tarnish our reputation by failing to deliver a project we have sold to our backers.

- A company that has transformed its processes to adapt to current constraints: The current crisis of confidence is rooted in the dubious financial practices of a large number of struggling companies. New campaigns have been used to fund the development and production of previous ones, which is only viable in a rapidly expanding sector. At the heart of this idea of “robbing Peter to pay Paul” is an inability to accurately assess the actual development costs of a project, or more precisely, its actual development time. The saying “Time is money” has never been truer than for project development in the crowdfunding world. Each month of additional delay leads to a huge spike in payroll costs, which are charged to the project underway. To definitively end this ultimately harmful approach, we have introduced a very simple rule: we do not launch a project until it is completely finished. We therefore know the development cost to the dollar and can match the product price to reflect the true total cost.

- A company that regularly reprints its products: Those who have followed Monolith for a while know that we regularly offer reprints of previous products during our campaigns. This can occasionally led to us being mocked for our “lack of renewal.” However, these multiple reprints are a major factor in our stability. After all, the profitability and deliverability of reprints are simply colossal, given the almost total absence of fixed costs (which are confined to the cost of on-page graphics and the work of our teams during the campaign itself). As a result, the campaign becomes both profitable and deliverable as soon as the MOQ (Minimum Order Quantity) is reached, which is often very low (between 400 and 800 copies!!!).

Conclusion

I know that this text was long and a bit technical in parts. However, I believe that it is crucial to explain, in very concrete terms and using examples, how unfortunately widespread practices in our sector have led to – and will continue to lead to – too many delivery failures and consequently to crises of confidence like the one that we are now dealing with. It was important to remind everyone that the main cause of failures is delays in project completion, which places a heavy burden on development costs. I can speak to this from personal experience, as Monolith has been very late on many projects (particularly the most recently delivered ones). By observing and measuring the impact of these delays on profitability, we were able to radically transform of our processes two years ago. Today, we are able to assure our backers that we will always be capable of delivering a project for which we have collected funding. Otherwise, we would not run a campaign to the end, and we would not collect any money. Our projects arrive on Kickstarter having already been completed and have been always been rigorously assessed for feasibility. Each project is watertight, leaving nothing to chance. I would therefore suggest that you be more selective when choosing the project owners to whom you entrust your money. And always trust rigor over glamor – at least until crowdfunding platforms finally apply stringent checks on the profits & losses of the projects they host and on the financial solidity of the owners, in order to provide backers with a guarantee of deliverability. To finish, in the next few weeks, I will be meeting with the heads of Kickstarter to discuss the roll-out of a policy of strict feasibility checks for projects, combined with a “labeling” system which would help backers judge the reliability of a project and its owners. I sincerely hope that they will listen to my proposals.

Thanks for reading me.

Fred Henry.